Devotion by Design was published to accompany the 2011 National Gallery London exhibition of Italian altarpieces before 1500. Written by Dr. Scott Nethersole, currently a lecturer in Italian Renaissance art at The Courtauld Institute, it provides a fascinating exploration of the challenges facing art historians involved in the study of altarpieces. That the volume manages to acknowledge these issues in the course of its presentation, and still remains accessible to a general audience is among its great strengths. The following review therefore, is an assay of the catalogue as a resource in its own right, and not a review of the exhibition.

Book design

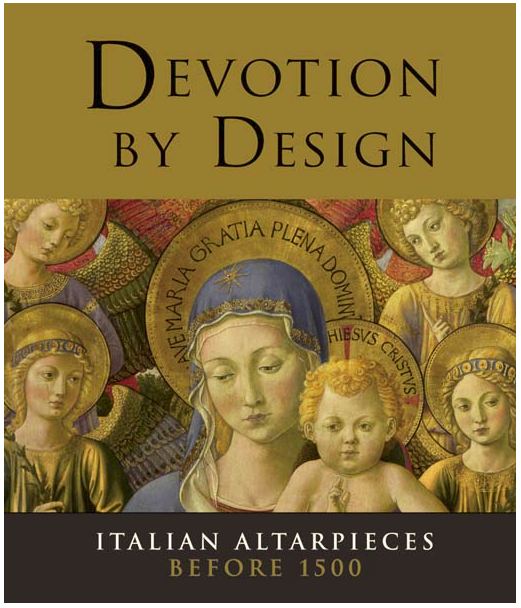

Unlike many catalogue volumes, Devotion by Design is not published in a large format. Its height is just under that of an A4 sheet and only slightly wider. Despite this smaller size, page space is fully utilised to display text and images. The quality of the images reproduced, and the schematic drawings showing altarpiece panels as they would have been seen in situ are particularly fascinating. Fitting with the gold leaf grounding seen in many altarpieces from the era in question, there is a recurring element of gold throughout the design of the book. The end of the volume contains a brief glossary, notes, bibliography and list of works, but lacks an index. This is unfortunate, as it made locating specific instances of an artist or theme a matter of guesswork rather than a quick search.

Schematic and central panel detail. San Pier Maggiore Altarpiece. c.1370-1

Content and contention

The period covered in the exhibition and catalogue is stated clearly in the introduction:

Other catalogues often have a selection of essays revolving around aspects of the central theme. When done well, such as in the previously reviewed Renaissance Faces catalogue, this interplay of themes can provide a depth to a volume that a single voice may not have. In Devotion by Design, Nethersole has gone to considerable effort to encompass the many facets of the study of altarpieces. Starting with the challenges of defining what an altarpiece actually is, he moves on to explore their structure, functional context and iconography:

This book considers Italian altarpieces in collection of the National Gallery and their role in the lives of people living in the Italian peninsula between the mid-thirteenth century and the year 1500.For an explanation as to why this period is so clearly demarcated, the foreword by gallery director Nicholas Penny provides more clues. Curatorial research conducted at the NGL has chosen to delineate the Renaissance into two periods: the early Renaissance and the sixteenth century. This is best reflected in the NGL publications Giotto to Dürer (1991) and Dürer to Veronese (1999). Hence it can be stated that Devotion by Design reflects the work done by the NGL into their altarpieces from this early Renaissance period. Whether there will be a forthcoming exhibition or publication for sixteenth century altarpieces is not mentioned.

Other catalogues often have a selection of essays revolving around aspects of the central theme. When done well, such as in the previously reviewed Renaissance Faces catalogue, this interplay of themes can provide a depth to a volume that a single voice may not have. In Devotion by Design, Nethersole has gone to considerable effort to encompass the many facets of the study of altarpieces. Starting with the challenges of defining what an altarpiece actually is, he moves on to explore their structure, functional context and iconography:

Since it cannot be reduced to a single definition, the altarpiece cannot be comprehended in terms of a single context or function. Indeed, it can be argued that the very validity of the category is questionable. For even if context and function could be fixed, we cannot be sure that the intentions of the patrons were followed or understood by the multitude of lay and ecclesiastical spectators, devotees and liturgical celebrants who prayed before altarpieces, glanced at or simply walked past them. What is more, a substantial number of 'devotional paintings' have survived whose function or purpose remains difficult to determine.

The result of this approach is successful overall, though even the non-specialist reader will detect that Nethersole seems less excited about certain aspects of this topic. The sections on construction of altarpieces are relatively dry - though it must be admitted - it is perhaps hard to write about altarpiece construction in an engaging manner?

This being said, each section of the book is replete with fascinating historical insights, related via information about surviving contracts and other pertinent documentary evidence. These intriguing glimpses into the 1400s really made for wonderful reading, and often were uniquely illustrative of the point being made:

The contract for Benozzo Gozzoli's Altarpiece of the Purification indicated that it was to be painted in likeness - in 'modo et forma' - of Fra Angelico's high altarpiece for San Marco in Florence. This was not a rare stipulation.

Benozzo Gozzoli's Altarpiece of Purification (top), painted modo et forma after Fra Angelico's San Marco Altarpiece (below)

All but the word estrangement

Published earlier in 2011, Marcia B. Hall's landmark The Sacred Image in the Age of Art adopted the Formalist concept of estrangement to describe deliberate efforts by artists to skew reality, either to highlight a sacred space, or by inclusion of symbolic devices to suggest a deeper level of meaning:

...Symbols in the Renaissance are always to some degree disguised to look as if they belong and only become noticeable on closer inspection....such symbols deepened the meaning and extended the viewers' attention as they puzzled over the significance of certain strange inclusions in the painting. There are multiple varieties of "making strange..." In the quattrocento, they are often iconographical anomalies or divergences from naturalism.

Tucked away in the section on Structure and Type of Devotion by Design is a remarkable exploration of the iconographic themes in works of this type. Perhaps because it was in accordance with my own interests, I found this segment of the book the most fascinating and eagerly re-read it on several occasions. It seemed to captivate the author as well, judging from the high amount of information successfully conveyed in a relatively short span of text. Offset with dazzling images, Nethersole quickly jumps from one example to the next, linking ideas and stylistic progressions between examples of devices used to convey a representational hierarchy or sacred space, including the introduction of antique and anachronistic elements to heighten this:

A quite different technique was used by Andrea Mantegna in The Virgin and Child with the Magdalen and Saint John the Baptist, where the two flanking figures tower over the seated Virgin. This type of composition, in which sacred company is assembled in a single space and on the same ground, is sometimes referred to as 'sacra conversazione' ('holy conversation'). However, the term is both anachronistic and incorrect, not least because inhabiting a single space, Mantegna has gone to some lengths to suggest a lack of community between the figures: they all look outwards and in a different direction, suggesting that each has a different focus of attention. Although Saint John's cloak brushes tantalisingly close to the Virgin's shoulder he does not acknowledge her presence. And while the Baptist and the Magdalen are of the same scale as the Virgin, the viewer is in no doubt as to her special position and role, seated as she is beneath a rich red canopy.

The Virgin and Child with the Magdalen and Saint John the Baptist c.1490-1505

This section was a delight to read, the only thing missing perhaps was the use of the word estrangement to summate these concepts, so successfully employed previously by Marcia B. Hall. This hardly detracts from the experience of the book in any way, though the increasing adoption of this term will be a topic we will return to in the upcoming review of Alexander Nagel's newly published The Controversy of Renaissance Art.

The final word

As a standalone resource, the Devotion by Design catalogue is an affordable and informative introductory text. Nethersole manages to convey the great challenges associated with this branch of art history in a manner that is visually engaging and peppered with documentary glimpses into the social factors shaping this mode of representation in art. For readers more familiar with the great works of the High Renaissance, this volume provides a fascinating glimpse of the prototyping that preceded the sixteenth century. With artists like Duccio, Mantegna and Gozzoli experimenting with sacred space, their relevance to the great iconographical constructs of Botticelli, Titian and later artists enables a deeper appreciation of these earlier forms.

References

Nethersole, S. Devotion by Design. National Gallery Company. 2011

Hall, M. B. The Sacred Image in the Age of Art. Yale University Press. 2011. pp.10-11

Many thanks to Inbooks Australia, National Gallery Company and Yale University Press for supplying a review copy of this volume.

9 comments:

Very nearly saw this exhibition when I was in London this summer. Now I wish I had!

I'll order this book for our library and will look forward to integrating some of the information from it into my lectures. I'm particularly curious about those contracts....

Cheers for the comment Ben - I found those historical tidbits fascinating too - they are mentioned throughout the book across the different sections. It is a shame you were in London and did not get to see it!

The exhibition is now closed, though there is a great video at the NGL YouTube channel for those interested:

Devotion by Design at the NGL [YouTube]

Episode 57 of the NGL podcast series also featured a preview of this exhibition

H

It was a tough decision. I had a limited amount of time in the Nat Gall and opted to see some old favourites (Van Eyck, Holbein, etc.). Tough call! Will definitely take a look at the video.

Actually I did have another question I wanted to ask you about the book. Why the 1500 cut-off date? Is it just a consequence of the conventional divvying up of the Renaissance into centuries, or was it something to do with the evolution of the altarpiece?

Cheers!

Ben

Cheers for the excellent follow up question Ben!

I have since updated the post to include the NGLs rationale for demarcating these time periods. There are stylistic nuances and historical considerations of course, but it seems Devotion by Design being cut off at 1500 fits in with how the NGL approaches the Renaissance from a research perspective.

Also, recalling M's comments on the Yale Press Caravaggio catalogue, I was dismayed to find that this volume also lacks an index!

Kind Regards

H

Very nice review, H! Yes, it is quite sad that this catalog lacks an index as well. It's so frustrating when that happens! You'd think that museums would be more attune to the needs of scholars.

I agree that that "estrangement" would have fit in nicely with the discussion in this catalog. I'm very familiar with the term "sacra conversazione," but I'm a little curious about Nethersole's mention that the term is anachronistic. I know that the visual convention of "sacra conversazione" developed in the Renaissance, but was that term coined after the Renaissance? I've never explored the origin of the term before. Does Nethersole say anything else about this anachronism?

Hi M! Thanks for the comment and intriguing questions. Nethersole does not spend a huge deal of time on anachronism - in that stated example the anachronism of course refers to adult figures of the John the Baptist and Magdalene appearing in a scene where Christ is still depicted as an infant.

In other depictions, such as those extrapolated from the apocrypha you will often see the Christ and the Baptist depicted as infants (a very common theme in Raphael's works for example).

There is some discussion in the Nethersole volume about the evolution of the Polyptych - where individual saints had their own panels or demarcated spaces. Duccio's 1311 Maesta is cited as a forerunner example of these boundaries being consolidated into a unified space, with later progressions gradually uniting the proximity of the saints and the Virgin to what was commonly described as a 'sacra conversazione'.

In fact, Fra Angelico's San Marco Altarpiece (in post above) is often described as a prototype to this type of depiction, which is why - as Nethersole states - contracts for other pieces often referred to the patrons' wish to have a 'modo et forma' variation of it.

As far as when the actual term 'sacra conversazione' was first applied - in 'Images and identity in fifteenth century Florence' Patricia Lee Rubin describes this term first appearing in eighteenth century inventories, and becoming common art historical parlance in the nineteenth century. (p.188)

Kind Regards

H

@M >> For more on Renaissance anachronism, you may want to track down Anachronic Renaissance by Wood & Nagel or its precursor article Interventions towards a new model of Renaissance anachronism - which you can get a open access pdf of here

H

Hi H! Thanks for the resources! The 18th and 19th century usage makes sense. I can see that the scene is anachronistic (as you described), too. If Nethersole had just described the scene (instead of the term) as anachronistic, I wouldn't have even raised an eyebrow!

Interesting point M! Nethersole did not supply this clarification between the scene and the term, but defers it to his bibliography - citing to see these refs on 'sacra conversazione':

*Rona Goffen's 1979 piece in The Art Bulletin - Nostra Conversatio in Caelis Est: Observations on the Sacra Conversazione in the Trecento link

*Peter Humfrey - The Altarpiece in Renaissance Venice - Yale Press (1993)

Kind Regards

H

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.